For nearly 10 years the unicorn StoreDot promised a breakthrough – a battery that charges in a few minutes. With no product on the market, their story proves a lesson for Israeli tech

Sagi CohenSend in e-mailSend in e-mailSend in e-mailSend in e-mailBatteries are a tough field and despite being among the first in the game, StoreDot is now lagging behindCredit:Eyal TouegSagi CohenIt was to have been the festive demonstration of a new and exciting battery. One hot day in 2019, a group of reporters gathered at the automotive technology convention in Tel Aviv. Facing them was the CEO of StoreDot, Doron Myersdorf, who presented his company’s great innovation – a superfast motorbike battery that can be recharged in five minutes. When the moment of truth came, a rider mounted the motorbike and turned on the ignition. But nothing happened. The motor remained silent. After a few long, embarrassing moments, and more attempts, the shocked audience was told that there was a problem. Behind the scenes, a backup battery was pulled out that had been charged ahead of time, and the motorbike revved up and went on its way.

StoreDot is not the first company to stumble during a demo, but this incident attests to the path this Israeli startup has trodden over the decade of its life: an ambitious vision, lots of hype and bombastic promises about smartphones that would charge in seconds and electric cars in a few minutes. But in reality, to this day none of this has come true.

The riddle of StoreDot is intriguing because its a unicorn that raised some $200 million over the years and was worth more than a billion dollars (at least on paper). To crack the case, we talked to people close to the company, former employees, people in the field and experts.

The story is complex: On the one hand, there’s a startup with a charismatic CEO with a vision, developing deep technology in a challenging realm. On the other, a company that did not fulfill its promises, has not managed to this day to put out a product, and has faced serious obstacles while working to cover up issues and pivot.

StoreDot was established in 2012 by Dr. Doron Myersdorf, Prof. Gil Rosenman and Prof. Simon Litsyn. The original idea was to develop displays and memory chips based on research by Prof. Ohad Gazit of Tel Aviv University, who discovered peptides (subunits of proteins) with unique energy characteristics. But in 2014, StoreDot revealed for the first time another idea, which sounded revolutionary: batteries for smartphones based on bioenergy components that could fully charge in a few minutes or even seconds.

A YouTube the company posted that demonstrated a smartphone charging in 30 seconds went viral and created the sense that the finished product was right around the corner. Articles were published in leading media outlets, and the company raised about $50 million from investors including Roman Abramovich and Samsung. Private investors also joined, among them high-profile figures like the late Nathan Milikowsky, cousin of former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and even Moshe Hogeg, who was on StoreDot’s board. Funds from China and even Israeli institutional investors like the teachers’ and kindergarten teachers’ pension funds got in on the action.

In 2015, Myersdorf promised that by 2016 the company would launch smartphones that fully charge in minutes. At the time, the company declared that it was turning to electric cars, because its technology made it possible to charge them in five minutes, and the first vehicles to use them would be on the road by 2021. It also revealed a new development: An LCD monitor based on the company’s organic technology that improves the colors and quality of display.

‘Can’t be done’

As these promises were being made, experts in the field expressed their doubts about StoreDot, among other things because its founders were not experts in the field of batteries: “Those in the field realized this was problematic. This battery is not simple and is actually very challenging - organic materials won’t hold up in it,” said one industry expert. And indeed, under the media radar, the company changed direction again, and a few years after its establishment it was now working on a battery based on germanium, a metalloid that was to have improved performance and allowed fast charging relative to other batteries. Later, this battery was given the internal name “Gen 1.”

Meanwhile, in 2017, StoreDot publicly focused only on electric cars. The company marketed itself by addressing one of the great stumbling blocks of the electric car industry – range anxiety – drivers’ fear of being stuck with a dead battery. The ability to charge an electric car battery in a flash, like filling up the tank at a gas station, is the missing link in the global electric vehicle revolution.

This marketing approach helped the company complete another impressive round of funding of $62 million at a valuation of half a billion dollars, with the participation of Samsung, Daimler-Mercedes (which was to have exclusively installed the batteries in its future electric cars), the Japanese multinational electronics corporation TDK and others. A year later, the round was expanded by another $20 million that came from BP. StoreDot demonstrated its charging capabilities at an exhibition in Berlin, and Myersdorf promised that in 2020, “millions of vehicles” with its battery would be on the road.

From 2018 to 2020, the company did demonstrations of its quick-charging battery on motor bikes and drones; it promised again that its smartphone battery that recharged in a minute was right around the corner; it talked about launching a backup battery for smartphones; it declared a collaboration with TDK, intended, it said, to bring StoreDot technology to the mobile market by 2019. Meanwhile, Myersdorf presented a far-reaching plan to raise $400 million to establish a battery factory in the U.S. by 2022.

But while StoreDot was shooting in all directions, it hit a wall. Even before putting one battery on the market, it turned out in its cutting-edge labs in Herzliya that the timetables were not realistic and the germanium battery was too expensive. Meanwhile, technological and scientific problems were also discovered. According to a few figures in the field, StoreDot was unable to find a formula to balance between the need for quick recharging and other parameters, like safety. The ability to demonstrate a battery that not only charged quickly but would also be long-lived and would not explode under physical pressure, turned out to be a complex matter. The company had some successes in the lab, but the first generation germanium-based battery never reached the market and work on it was stopped.

“The vision of five-minute charging led to things that in principle were impossible to do,” says one ex-employee. “Any battery can charge in five minutes but there are compromises in terms of the life of the battery, heating up, density. You have to manage these compromises, and the blanket is short. Although in experiments we reached performances that aren’t on the market, the problem is that you can present the craziest battery there is, and if it explodes, it will wipe out the company.”

In a media interview in 2019, Myersdorf claimed that the delay in the manufacture of the smartphone battery stemmed from a shortage of required materials. But in conversation with us for this article, Myersdorf raised a surprising claim: the Gen 1 battery, whose development required many years and tens of millions of dollars, was only intended to prove feasibility. “The goal of the first generation was to prove that the impossible could be done, and not to create significant business,” he says.

At face value, this claim contradicts StoreDot’s past statements. To this Myersdorf responds: “Tactically I wanted to put the first generation out on the market in order to show some revenue, because there was pressure from the board. After all, every investor pushes in a different direction, and in order to satisfy some of the actors, I said let’s put out the first generation because we already had batteries and orders.”

Myersdorf places the blame on the partners and customers for the battery not reaching the market. He claims that Samsung wanted to integrate StoreDot’s battery into its mobile devices, but backed out after an exploding batteries affair. Daimler, he claims, also stepped back when it decided to focus on the driving range of its electronic fleet - and not its charging speed.

Another factor, he says, is the surrounding market. “I thought Storedot would stand out and be the only one to offer five-minute charging. Pretty soon they started to copy me. I had to raise the bar to differentiate ourselves. I had to prove that I was better than the rest. It took a longer time than we thought.”

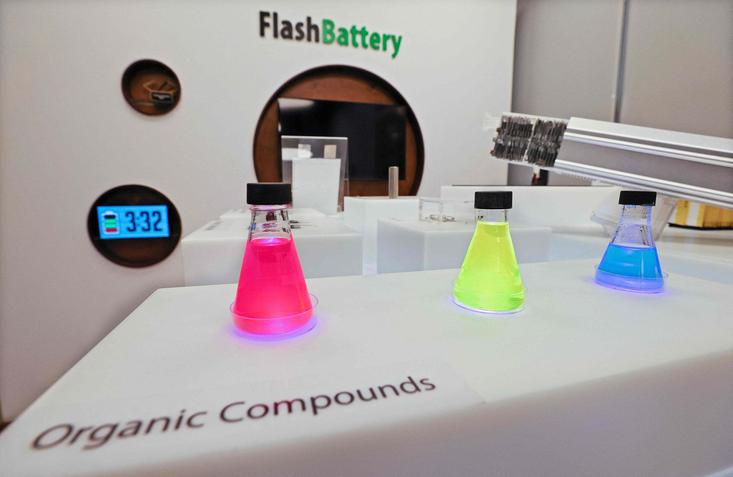

The plan from 2015, to launch advanced monitors based on organic components likewise yielded no product. In 2019 a new company was spun off from StoreDot, named Moleculed, which according to its website “develops organic compounds” for two markets: Monitors and cannabis cultivation. Hezy Rothman was appointed as CEO, but left the company last year, and the company currently has no employees listed. According to Myersdorf, the company wishes to sell the IP and patents it holds. Rothman declined comment.

Challenging the laws of physics

In 2019 StoreDot made a major strategic decision: To focus solely on electric vehicles and relinquish all other business ventures. Thus the company once again changed directions, now focusing on development of its second generation battery: 2Gen, as a silicon-based battery for electric vehicles (silicon being a “related” element to germanium.)

Myersdorf describes the switch as natural evolution, claiming the company has used a variety of materials in its developments over the years. StoreDot also claims that its batteries do include organic compounds. And yet, a field expert stresses that the switch from germanium to silicon is a fundamental technological change, done too slow and too late, with many companies in the field already in a race to develop silicon-based batteries, or even more advanced technologies. These batteries use silicon instead of the carbonic material known as graphite, which is used in ordinary batteries. The problem is that silicon is an unstable material that tends to bloat and crack, and many companies in the market are already working to address this.

The technological challenges are immense, and industry sources define the attempt to create a silicon battery as “an attempt to beat the laws of physics.” The bottom line, as an industry source explains, is that although StoreDot was a pioneer in the field, a decade later, they are just where they started from a business and commercial standpoint. Meanwhile, the market has jumped ahead: “It’s a huge missed opportunity,” he said.

StoreDot currently employs 116 workers. In November it announced that it has successfully managed to manufacture rapid-charging silicone batteries for vehicles with its Chinese manufacturing partner, EVE, and that it was sending preliminary samples to automakers. StoreDot’s updated goal was to reach mass commercial production by 2024.

What can this battery do? Here, again, it depends whom you ask: Between 2015-2019 StoreDot presented a revolutionary vision wherein its battery will enable a 300 mile drive after a mere five minute charge.

Early last year, in an interview, Myersdorf showed more humble figures: 20 miles of driving range charged per minute, so that a five minute charge would give the car a 100 mile, or 160km range. “Within five minutes a driver will be able to go get a cup of coffee and get 100 miles of driving range,” he said. Since mid-2021, StoreDot no longer speaks of minutes and miles, rather declaring that its battery will eventually allow “a 50 percent reduction in charging time,” compared to current market standards. According to Myersdorf, the change is semantic – the company stands by its promise of 100 miles range charged in five minutes.

“In fact our chemistry allows us to charge the entire battery in five minutes,” he explains, “but there are other factors, such as the charging stations and the grid, that constitute the limitation – not StoreDot’s technology. That’s why I tailor the story of the value offered to what the ecosystem can do.”

StoreDot needs a lot of money to reach its goals. Myersdorf says they want to raise 400-500 million dollars to build factories in a joint venture with other manufacturers.

In March 2021 came reports that StoreDot was mulling going public through a merger with a SPAC, at a valuation of billions of dollars. According to Myersdorf, these plans have been abandoned for moment due to market volatility. Instead, in early 2022 the company announced a fundraising round of “up to 80 million dollars.” The fundraising round has brought StoreDot to unicorn levels, he says, with a valuation of over a billion dollars.

The latest round was led by a Vietnamese electric vehicle maker named VinFast – a young company with big plans, trying to break into the American market. Two large and strategic StoreDot investors, Samsung and Daimler, did not take part. Investor BP did. The round is still ongoing.

The absence of a large and established automaker is eyebrow-raising, escpailyl as 2021 saw the world’s major automakers invested fortunes in other startups developing innovative batteries.

Myersdorf brushes off the doubts. “The company investing in StoreDot may be Vietnamese, but its vehicles sell in California. It’s an aggressive company that’s building battery factories. They have a startup mentality that doesn’t move slowly like the giants, but runs fast to get rapid charging in. They fit us like a glove.”

Even if it meets the schedules this time, StoreDot’s challenge in the competitive field of batteries for self-driving vehicles is mounting. “The automakers will put the battery companies through hell,” says an industry source. “You can’t enter the auto market as a startup with a preliminary product. They’re going to want to work with an experienced manufacturer.”

StoreDot is operating in a crowded and competitive environment. Many companies, from little startups to giants such as Tesla and Toyota, are investing vast sums in battery technology. The hottest technology at the moment is “solid state,” which is supposed to improve performance dramatically – although years will be needed for the technology to mature. StoreDot, still working on bringing its silicon battery to market, also declares its intent to launch a solid state (3Gen) battery in 2028.

Israeli hubris?

Myersdrof, a first-rate marketing professional, has managed to convince investors, clients, partners, and journalists of his vision. Over the years, the company has been steadily increasing its workforce, and many of the workers past and present speak of him with great respect. They tell of how when doubts would arise in the company, he would gather his employees and share his experiences as an executive at EM systems, Dov Moran’s company that invented the disk-on-key and was sold to Sandisk. Then, too, he would tell them about how a small Israeli company changed the world against all odds.

“Israelis are used to hearing about massive fundraising by companies that have made two features,” says a former employee. “People don’t understand how long, hard, and complex a process it is to develop a battery. I don’t think anyone in Israel realizes this.”

Myersdorf, to this day, sounds utterly convinced: “I’m always authentic and tell the truth. StoreDot is Tesla plus. Elon Musk is my role model. He changes the world and doesn’t care what people think. We’re authentic, but the market is changing, and every time you do the best you can with the knowledge you have. When I said that we’re going to launch in a year with Samsung and Daimler, that’s what they said too. You have to understand that this world is in motion. Apple is working on a self-driving electric car. Apple can come, put down 10 billion dollars and buy StoreDot because we have something nobody else has. Will we sell? I’m not sure.”

Even if he eventually succeeds, industry figures point out the negative impact caused to the industry and the entire field by StoreDot’s unrealized hype: The creation of non-credible progress rate presentations, they say, produced irrational expectations of other companies in the field, and some entrepreneurs claim that this is one of the reasons investors have stayed away from other Israeli battery companies over the past decade.

Startups spreading empty promises, before they know for sure they can deliver, practice what is known as “fake it till you make it.” StoreDot has taken this method to the extreme. Time and again Myersdorf outwardly presented far-reaching promises, never realized. This enabled him to keep the company’s narrative fueled, creating the sense that the big breakthrough is just around the corner. Over the years StoreDot has reminded many of Better Place, a startup that raised hundreds of millions of dollars for an ambitious vision of revolutionizing the EV market. In the case of Better Place, it ended in tears: The company shut down and burned its investors’ cash.

StoreDot in response says: “StoreDot, considered a world leader in battery technology, has over the years led Israel to the forefront of energy science, and in particular to the breakthrough of full charging of lithium-ion batteries in minutes, which was considered impossible, without significantly compromising the energy density determining the driving range. The development process of such groundbreaking technology requires significant outlay of research resources over long periods of time, which due to the complexity does not necessarily yield instant success, thus requiring determination and persistence in achieving the long-term vision.

“The company has been wise to adjust and focus its technology and patents which it has developed to the enormous and rapidly growing EV market, and is therefore receiving growing interest and support from auto giants which have examined the technology in depth and have entered as strategic partners with ever-increasing investments in StoreDot and its vision. We are proud of the road we have gone to advance research and industry in Israel and to bring the future of transportation closer to a new and clean zero carbon emissions reality.”